The great question, when writing one of these, is how much do I assume you've read of the story in question? If I assume none, then I have to rehash the plot. Which bores some people (like me). If I assume all, then I completely skip the plot and trust you to zip ahead with me. Which frustrates some people (who need the structure of the plot). Here's to hoping for a happy medium...

As I mentioned in the last post, the ending of this story is astonishingly satisfying. To get there, however, we do have to trudge the path of the plot's build-up and resolution. Why? Because we, the readers, are in on the dramatic irony of the story. (This means that the reader has more information than the characters.) Often used in omniscient storytelling, dramatic irony gives the reader insight or feelings that the characters themselves lack. In this case, we build up a particular set of feelings towards the king.

As the antagonist of the story, it is hardly surprising that the king inserts himself early in the story. And tried to kill a helpless baby. Honestly, who's going to love the king after that? In an astonishing show of grace (or fate), the babe survives and grows up to be an admirable young man. Fun, hard-working, lovable, and outgoing, our hero is destined for great things. (Thanks to dramatic irony, we knows of the midwife's prophecy about the child, which only one other character knows about.)

When the king returns and sets up the hero to be executed, we're already primed to hate the king for this. It is no hardship to cheer the boy and his unexpected friends and helpers along the way, but the king's long shadow hovers over the story. Whatever will become of a good boy who is hunted by such a ruthless jerk?

The boy then goes on his adventure through the forest, once again propelled by the king who wants to kill him. On the one hand, shouldn't the king get the message that this boy cannot be murdered by indirect means? On the other, however, is our hero going to have to arrange for his own father-in-law's death? Let's hope not...

In the end, however, it is the surprising twist of how the hero handles the king that we find so satisfying. We like that he doesn't stoop to killing the king. We like that he is never faced with the truth of how many times the king tried to do away with him. We like that the king, instead, is punished by his own actions. The boy has only to make good use of the king's greed.

Parts of this story are found in a lot of modern stories. Especially ones written with boys in mind for an audience. The appeal of outsmarting a devious opponent is universal. Jeffery Archer does it in books like A Matter of Honor or Honor Among Thieves, surprising his readers continually with good, loyal characters who beat the bad buys at their own games. Some modern authors beat the bad guys by destroying the game. Break the rules so badly that the game can never be played again, or kill the one character who makes the game work. (Hunger Games, Matrix trilogy, need I go on?) But as a good writer, how can you get your character out of this bad situation with some good character still intact? Killing a wicked character can feel good, but it's fleeting when compared to a story where good didn't just survive. Good triumphed.

But that's a story for another day...

Tuesday, October 16

Wednesday, May 9

The Devil, Three Golden Hairs, and...

Twice this week I’ve written

the same entry on "Jack and the Beanstalk", only to have my computer eat it

before I could save it. It will write itself again. Mentioning devils who still

live with their mothers last week kind of behooves me to dig into that story

this week.

“The Devil’s Three Golden Hairs”

is another fairy-tale-less-traveled that I love. The rhythm lends itself to

telling aloud—preferably around a smoky fire with a bunch of snickering friends—and

the plot takes some nice, unexpected turns. The archetypes in this one are

different from what is usually found in fairy tales. This is almost another “soldier

of fortune” fairy tale—but the youth of our hero fudges that line. There are

actually several similar Russian fairy tales (a culture, like the Celts, with

murky ties to age), but the German one is the most appropriate for this week.

Unlikely though it might seem

if you’ve never read this story before, many of the motifs are common

denominators in modern fiction. Aside from it being an entirely likeable story

with easily drawn characters, the story has certain values that are universal.

Given your background, you

might find rooting for the underdog the most familiar. Or the rags-to-riches

aspect. What I’ll be focusing on this week is why most readers find the ending

so satisfying.

What do you think…?

Wednesday, May 2

On Returning and Indexing...

Oh, I give up! Weeks I spend, wrestling with this fascinating, nascent concept offered by Hansel and Gretel—because it’s been hovering over my head for a good two months—and it won’t come. The $*&# thing refuses to be written. I have notes I’ll come back to, but I’ve had more than enough of that.

We’ll resume regularly scheduled fairy tales next week. Before we go further, I’d like to cover the Aarne-Thompson system with you a little. It’s a helpful tool, but that doesn’t mean it can’t also be confusing.

Of all the folk tales in all the world, some of them are very similar. Some have nothing in common, but the whole point of labeling something a “fairy tale” (see the Genres page for additional context) is that it connects to the human soul. A fairy tale (or folk tale) contains clues about the values and character traits of a culture. Not necessarily religious beliefs—as some fairy tales incorporate culturally “lost” elements, such as fairy godmothers or devils who still live with their mothers. (Yes, really. One of my favorites. Coming soon...)

People will often complain that “all fairy tales are alike.” It’s where we get phrases like “fairy-tale endings” and “happily ever after.” But these stories aren’t all the same. We’ve seen stories about very young people, and very old people. Characters who change and characters who don’t. Or won’t. And while Red Riding Hood has very little in common with Cinderella, but readers all know a “damsel in distress” when they come across one in stories.

These things in common are called “motifs”—meaning patterns. In folk tales, motifs are events or actions by a particular character that make a recognizable design. All of the parts of a fairy tale don’t have to be the same, but when certain scripts show up, labels are easy to apply.

Cinderella is an unbelievably popular tale, but Snow White is a more interesting example here. A couple variations are stashed in the Summaries page. In both the German Snow White and the Scottish Silver-Tree, there is a “mother figure” out to kill our heroine, an escape to a place where the princess is loved, a glass box in which the “dead girl” is hidden, and a miraculous recovery facilitated by a third-party woman. Oh, and a prince whose love for our girl knows neither time nor reason. There are even a couple Italian versions I have not included, all with the same motifs. (The two Italian versions, one is very complicated and the other is very distressing. The latter also has certain motifs in common with “The Goose Girl.”)

Antti Aarne, and later Stith Thompson, developed this index which tracks the patterns of a story. Their studies focused primarily on Northern European and Western Asian stories, but not exclusively. In recent years, a scholar named Hans-Jörg Uther has adapted the indexing system so it can be expanded to include new material, but this has not taken universal hold.

The Aarne-Thompson classification system is designed a little like the Dewey Decimal System in American libraries. Big categories are grouped by the hundreds, then more detailed motifs are subdivided in each category until each story has its own unique number. The Persecuted Heroine, for example, is labeled “510A”—this story is also known as the Cinderella archetype. Supernatural helpers, like fairy godmothers or magic sticks (from “Katie Wooden-cloak”), are the 500 category, and a girl who needs supernatural help is the 10 of 510. “A” and “B” are further subdivisions—510B is a category of stories where good girls are escaping from abnormal circumstances. Animals stories have their own category. So do ogres.

Like any indexing system, it’s not perfect. But it’s still a very useful tool when exploring how to study or think about a fairy tale.

What are some “modern fairy tales” that have motifs from older fairy tales? Can you think of recent stories where the pattern of a particular fairy tale was disrupted to make the story different? How effective were the changes?

Thursday, April 5

The White Snake and Some Personal History

Where last we left our heroine, we hadn’t met her yet. We were marching to the beat of a different drummer, walking beside a man we’d all met before. He was capable, resourceful, and looking for a place to lay his loyalty. This man can be found in a wide range of genres, appealing to almost every demographic. Except, perhaps, young children.

You have to learn a little bit about loyalty and its value before you can read about its loss.

A soldier of fortune could also be called a mercenary, but this has negative connotations. When you say “merc”, people think of pirates and Hessians and lots of sadly failed coups across the world. Rightly so. But a soldier of fortune has left that business. For whatever wonderful reason, the human mind is more forgiving of and receptive to someone who is looking for a new start in life.

Point number one in favor of “The White Snake”—it’s about a former servant. Servant, farmer, soldier—the man who wants his new life has already had one. Unlike fairy tales about younger sons (a topic for another story, surely), soldier of fortune stories are about men with pasts. Grown-ups. They may not mature or change on the page, but their previous experience tempers their reactions to the fairy tale’s adventures.

Point number two is that this IS a new life. This story isn’t a young prince looking for a new kingdom to take over. Instead, we read about someone whose old life doesn’t necessarily fit with his new ambitions. Some of his old skill set may apply—attention to detail, responsibility, his well-honed ability to delegate—but new aptitudes and talents must be uncovered. Or our hero will die.

Nice and melodramatic, that.

Point number three is this soldier of fortune’s commitment to his new quest. While he comes with a past, it isn’t a past that ties him down. Having served faithfully before, he is now free to commit himself wholeheartedly and with full knowledge of what he’s doing. He might not have every answer for every situation, but he isn’t a man who will abandon his honor.

When we take a look at other soldier of fortune stories, there will be other aspects to ponder. These three from “The White Snake” are relevant because of how often we see echoes of them in modern stories. Heroes, looking for homes. Champions, in search of a cause. And (to paraphrase the immortal Jane Austen) husbands, in want of wives.

These soldiers of fortune are men with pasts, but these pasts fuel their drive to find a future.

As writers, we can get so wrapped around a character’s backstory that it takes up more of the tale than the actual adventure. In “The White Snake,” the servant’s quest to become a king and a husband is the latter third of the tale. Not the bulk of it. One of the side benefits of oral stories—plenty of time to soften the audience’s sympathies toward a favorite character.

The problem of backstory, illustrated with this fairy tale, is one of determining your goal for the story. Because the servant’s history before the kingdom contest is so much of the story, all the author has room for is the conclusion of the quest. We’ll see other soldier of fortune stories where backstory is not provided, and as such the reader can devote much more emotional energy to the “happily ever after” of the characters. Countless how-to books will tell young authors when and how much backstory should be applied, but you must consider the weight of it. If there is so much of it and it is so essential, as in this case, perhaps the story should be more about the backstory than the final quest.

M.M. Kaye, who I mentioned in an earlier post, grew up to write a few other novels. One of which (a personal favorite) starts with five chapters of backstory on one character. Then anywhere between a paragraph and three pages of backstory for each character she introduces. Small wonder The Shadow of the Moon weighs so much. And yes, she does have soldiers of fortune in her stories. Margaret Mitchell, who wrote in a similar vein a generation prior, didn’t dwell as much on the character’s backstory in Gone With the Wind, but she does provide copious historical backstory all throughout the plot.

It’s a style that’s discouraged today, but the problem never goes away for writers. To tell, or not to tell—and how much.

But that’s a question for another day...

Monday, April 2

The White Snake and...

“Once upon a time...” there lived a fair maid. Or a pampered princess. Or an out-of-step girl. To date, every story we’ve discussed all have one thing in common: female protagonists. According to the world population—and the most likely candidate to tell a nursery story—we should not be surprised. If more than half the world’s population is female, and the author of a story MUST choose a central character, then it follows that the majority of fairy tales should star females.

Happily, they don’t always.

Some of the most interesting fairy tales are “soldier of fortune” stories. The main character is generally male, often poor or footloose, and looking for adventure. Or whatever comes his way, to quote an old 70’s song. “The White Snake” is one such tale.

Some stories, when read in their entirety (instead of the chopped-off summaries I provide), are meant to be told aloud. Again, this should make sense. Many old stories were passed down orally, by people who had neither time nor education to learn to read. To help the teller’s memory and the audience’s participation, these stories frequently have a trademark rhythm. Events, or speeches, happen repeatedly in cycles that are easy to remember and mimic.

Now, The White Snake would be memorable even without the rhythm of questions and offers. Even without any names in the story, this is a tale you could pick out of any line-up in any suspicious editor’s office. The frame of the story is not so amazingly unique that it could never be mistaken for anything else. Why, then, could the reader always identify it?

There are specific elements of the story that make it unique—if only for the order in which they happen—but more on that next time. Ponder some stories you know that feature boys (or men) who are strong, smart, and in search of a home. Can you think of a lot, or only a few? Especially in certain genres, these male characters may not be the central protagonist, though they often appear as heroes in certain female fantasy genres.

If we don’t read a lot of this kind of fairy tale, then why do we find so many soldiers of fortune in our modern stories?

Monday, March 26

Jesus and the Dynamic Character

Students of the craft of writing often divide their characters into two camps--protagonists and antagonists. This isn't wrong. It can be limiting, however, when the lines between the camps aren't so black and white. Sometimes, the goals of the different characters are so diametrically opposed that it cannot be argued that the characters are even on different sides.

Take, for example, the story of Jesus' visit to Sychar. (A village in ancient Samaria where Jacob's Well was located.) Antagonists are hard to find in this historical account. But characters abound. And these characters can be divided into two very clear camps: static and dynamic characters.

A static character is one whose nature and traits do not change between her first introduction on the page and the last glimpse the reader has of her. A dynamic character does change. Within the writing community, there is an assumption that dynamic characters are good, and static characters are bad. This assumption is made on the belief that readers always want their main characters to change.

And you know what "they" say about assumptions...

As we have seen over the last weeks, characters with flaws are appealing to the human psyche. (Yes, really. See Rapunzel if you missed it the first time around.) But we have also seen that protagonists don't have to change to be universally loved. (See Cinderella for that argument.) Some of the characters in John 4 are static, and others are dynamic. This story, written by the best Author, expresses both the changes and the immovability of the characters through dialogue and interaction.

Jesus: A static character if ever you've met one. This man Does Not Change. Which isn't bad. If this story is your first encounter with him, you might want to read further, but from his first breath on the page, he is committed to one goal, one purpose, one way. How that commitment plays out in his interaction with other people depends on the person. With the woman, he invites her to speak. He then answers her question in a fashion that gives her the freedom to ask another question. Anything she likes. He discovers in her a deep desire for truth, and a hopelessness that it can never be hers, and answers her heart. Not her sins. Not her past. He has come looking for her soul. (Calvin Miller does a wonderful interpretation of this in his poem The Singer, chapter XI.)

His goals do not change when others enter the scene--be they his beloved disciples, or the townspeople who do not know what to believe. But being a static character does not make him less of a powerful force in this story. His goal will not change if his audience rejects it, but both the giver and the receiver in such a conversation would come away profoundly marked by the interaction.

The Woman: Our darling dynamic character. When she enters the story, she is alone. Friendless, even for having had a string of intimate relationships. Jesus does not offer to become part of this string--or even replace it. He offers her truth, where until now she has heard only lies. The freedom and joy with which she responds profoundly mark her for the rest of her life.

When she arrives at the well, it is the middle of the day. Any sensible woman would have gone to the well at dawn, before the day was hot and household chores needed attention. But this woman wasn't welcome with others, so she came alone. This one conversation with Jesus releases her from the shame of her past choices, so that she can run into town to find the people who do not speak to her and say, "Come and meet a man who knows my secrets." The townspeople already know her secrets--this is not a surprise. But they don't know her joy. This is new. Worth investigating.

The Disciples: These fellas are such an interesting bag of tricks. Dividing them into static and dynamic individually is easy (Thomas, Peter, John, Judas), but as a group? Best to side with static in this instance. When they find Jesus freely talking with a fallen woman, righteousness demands a certain code of conduct. Withdrawal. Concern. Perhaps even a little preaching. Jesus does not rebuke them outright, but neither do we observe a change in their understanding. Their questions indicate their own search for truth, echoed in the woman's enthusiastic evangelism.

The disciples, unlike the woman, have chosen their giver of truth. They are out to follow their rabbi, wherever that teaching may lead. That doesn't stop them from expecting him to follow their code of standards, but it does open their minds to the possibility of Jesus changing their standards to match his. As with almost every other account of the disciples' interaction with Jesus, these characters are on a long, slow journey to change. Sufficiently slow that their individual characters can be measured.*

The Townspeople: Like the woman, these are also dynamic characters, though on a lesser scale than she. Their response to Jesus' teaching is to him, not to the world around them. Where she rushed to invite people--friends, strangers, enemies--to see him, they rush to pursue him. Again, this isn't bad. A writer who shows that some people are changed profoundly by an encounter with Jesus, while others react to a lesser degree, tells a very real story. Not every character will respond to another character in the same way. Writers who fail to take this into account do their readers a great disservice.

This story, like many of the fairy tales we've covered so far, begs the question of a reader's response. Reading a story does not have to change the reader. But it could. A reader is not required to be a force of change in her world. But she could. In this story, both Jesus and the woman moved others around them to change. Not because they were both dynamic characters, but because both characters demanded a response from the other characters in the story.

Like the woman at the well, writers and readers are at a crossroads. We can choose to change--or not. We can choose to challenge others to change--or not. Having made the choice, where will the next road take you?

*In my small understanding, there are two exceptions to this: Nathaniel, called Bartholomew, and Jude the Lesser, called Thaddeus. My personal studies have shown that these disciples' decisions to change and responses to their choices were profoundly different. (In your own studies, you might find other disciples whose lives affect you differently.) Why? That is very much a story for another day...

A static character is one whose nature and traits do not change between her first introduction on the page and the last glimpse the reader has of her. A dynamic character does change. Within the writing community, there is an assumption that dynamic characters are good, and static characters are bad. This assumption is made on the belief that readers always want their main characters to change.

And you know what "they" say about assumptions...

As we have seen over the last weeks, characters with flaws are appealing to the human psyche. (Yes, really. See Rapunzel if you missed it the first time around.) But we have also seen that protagonists don't have to change to be universally loved. (See Cinderella for that argument.) Some of the characters in John 4 are static, and others are dynamic. This story, written by the best Author, expresses both the changes and the immovability of the characters through dialogue and interaction.

Jesus: A static character if ever you've met one. This man Does Not Change. Which isn't bad. If this story is your first encounter with him, you might want to read further, but from his first breath on the page, he is committed to one goal, one purpose, one way. How that commitment plays out in his interaction with other people depends on the person. With the woman, he invites her to speak. He then answers her question in a fashion that gives her the freedom to ask another question. Anything she likes. He discovers in her a deep desire for truth, and a hopelessness that it can never be hers, and answers her heart. Not her sins. Not her past. He has come looking for her soul. (Calvin Miller does a wonderful interpretation of this in his poem The Singer, chapter XI.)

His goals do not change when others enter the scene--be they his beloved disciples, or the townspeople who do not know what to believe. But being a static character does not make him less of a powerful force in this story. His goal will not change if his audience rejects it, but both the giver and the receiver in such a conversation would come away profoundly marked by the interaction.

The Woman: Our darling dynamic character. When she enters the story, she is alone. Friendless, even for having had a string of intimate relationships. Jesus does not offer to become part of this string--or even replace it. He offers her truth, where until now she has heard only lies. The freedom and joy with which she responds profoundly mark her for the rest of her life.

When she arrives at the well, it is the middle of the day. Any sensible woman would have gone to the well at dawn, before the day was hot and household chores needed attention. But this woman wasn't welcome with others, so she came alone. This one conversation with Jesus releases her from the shame of her past choices, so that she can run into town to find the people who do not speak to her and say, "Come and meet a man who knows my secrets." The townspeople already know her secrets--this is not a surprise. But they don't know her joy. This is new. Worth investigating.

The Disciples: These fellas are such an interesting bag of tricks. Dividing them into static and dynamic individually is easy (Thomas, Peter, John, Judas), but as a group? Best to side with static in this instance. When they find Jesus freely talking with a fallen woman, righteousness demands a certain code of conduct. Withdrawal. Concern. Perhaps even a little preaching. Jesus does not rebuke them outright, but neither do we observe a change in their understanding. Their questions indicate their own search for truth, echoed in the woman's enthusiastic evangelism.

The disciples, unlike the woman, have chosen their giver of truth. They are out to follow their rabbi, wherever that teaching may lead. That doesn't stop them from expecting him to follow their code of standards, but it does open their minds to the possibility of Jesus changing their standards to match his. As with almost every other account of the disciples' interaction with Jesus, these characters are on a long, slow journey to change. Sufficiently slow that their individual characters can be measured.*

The Townspeople: Like the woman, these are also dynamic characters, though on a lesser scale than she. Their response to Jesus' teaching is to him, not to the world around them. Where she rushed to invite people--friends, strangers, enemies--to see him, they rush to pursue him. Again, this isn't bad. A writer who shows that some people are changed profoundly by an encounter with Jesus, while others react to a lesser degree, tells a very real story. Not every character will respond to another character in the same way. Writers who fail to take this into account do their readers a great disservice.

This story, like many of the fairy tales we've covered so far, begs the question of a reader's response. Reading a story does not have to change the reader. But it could. A reader is not required to be a force of change in her world. But she could. In this story, both Jesus and the woman moved others around them to change. Not because they were both dynamic characters, but because both characters demanded a response from the other characters in the story.

Like the woman at the well, writers and readers are at a crossroads. We can choose to change--or not. We can choose to challenge others to change--or not. Having made the choice, where will the next road take you?

*In my small understanding, there are two exceptions to this: Nathaniel, called Bartholomew, and Jude the Lesser, called Thaddeus. My personal studies have shown that these disciples' decisions to change and responses to their choices were profoundly different. (In your own studies, you might find other disciples whose lives affect you differently.) Why? That is very much a story for another day...

Friday, March 23

Beauty, the Beast, and Great Expectations

When last we left our heroine, she had bargained herself to save her father. Woe unto her, for her life was over! Or is it...

Whether young Beauty went into the castle expecting to be executed is anyone’s guess. She might (reasonably) have expected imprisonment. Without a doubt, she should not have expected to be made mistress of the castle upon her arrival. Unless, of course, she’d heard this story before.

Then, she could expect to be handed the keys immediately, and her reign of terror—you know, hearts, butterflies, and cuppy-cake gumdrops—could commence. The beast would be her eternal slave, and she would never want for anything.

Hmm. Perhaps she didn’t expect the royal treatment she received.

The impression I get from the frame of the story is that Beauty does not enter into the bargain with great expectations. But I do believe she develops some as the story progresses. She does not ask for much initially, though the beast insists on giving her everything he can. Especially his hand in marriage.

Whether or not that offer is much of a bargain is open to debate. As with the prince in the story of Sleeping Beauty, the beast’s rapid attachment and lack of relationship-developing obstacles present the reader with good reason to be suspicious. As Beauty chooses not to capitulate to the inevitable so quickly, she must have some other expectation for her life.

Or else she didn’t get the memo.

Beauty, as is NORMAL for a young girl, does not start out her life expecting to marry a beast. Time and exposure to one do not change that expectation. She still won’t marry him. (In some versions, Beauty has nightly dreams of a handsome prince who wants to know why she doesn’t love him. If that’s not an invitation to psychoanalysis, I will eat my hat.) Even when she begins to realize that she—the beast’s prisoner—can ask for a vacation—or, let’s be honest, anything she wants—she still does not want to marry the beast. “He’s just a friend.”

When she returns from being away (sometimes by magic, sometimes by a hard journey), the beast does manage to get her to say “I love you.” Not an acceptance of his many proposals, but close enough for government work. Or a curse, in this case. But still, Beauty doesn’t agree to marry a beast. She agrees to marry the handsome prince he turns into, once the spell is lifted.

This is always the part that worries me. The part in “fairy tales” where girls agree to marry the handsome princes that the beasts, toads, or other monsters “revert to” once the curse is gone. We see this in a lot of other stories. Robin McKinley likes this story so much she rewrote it twice (Beauty and Rose Daughter). Pride and Prejudice, where Elizabeth does not agree to marry Darcy until he transforms into a kind, generous man. Don’t get me wrong—there are many, many things I love about Jane Austen—but this aspect of the fairy tale bothers me.

If you give a girl a hero who has to change in order to get that ring on her finger, what is that going to do to the reader’s expectations in her own everyday fairy tales? Will a reader really go around kissing frogs until one just happens to turn into a prince? What if he stays a beast? What if he’s smart enough to pull a bait-and-switch? (A fraudulent method of convincing someone to buy the wrong thing for too much.)

And what will this do to all the Perfectly Normal Beasts out there? (“What’s wrong with them?” “Not a thing. It’s why they’re called Perfectly Normal.” Gotta love Douglas Adams at his most obscure...) Is this a fairy tale that will damage the reader to the point of damaging her future relationships?

Hate to leave you hanging, but that’s a story for another day.

Or, perhaps, one you should write. To correct that wrong...

Monday, March 19

Beauty, the Beast, and...

Once there was a girl, so brave, so true, that her willingness to sacrifice herself for someone she loved changed the heart of a great and terrible beast. Who was actually a cursed prince. And then they live happily ever after. Yes, this one is an old, familiar tale.

Which some people I know like to argue is the most Christ-like of the major fairy tales, because of the sacrifice substitution. And some other people I know like to argue is entirely about limited opportunities and Stockholm Syndrome.* Clearly, Beauty and the Beast is one of those stories that depends a great deal on the reader’s point of view.

Sadly, I won’t be discussing point of view this week. When Alex Flinn’s Beastly became a motion picture last year, point of view (or POV, for short) suddenly became a relevant part of fairy tales. Mostly because she writes from unusual POVs (the beast, the ugly stepsister, and so on). It’s an interesting concept, but it’s better discussed with other fairy tales. Maybe later.

No, this week I want to focus on young Beauty. As a writer, you are sometimes left with the very serious decision of what to reveal in a story, and what to leave out. Beauty’s motivation in agreeing to the trade—herself for her father—is an easy one for a reader to trace. Had she thought about the permanence of this choice? What if the beast ate her? What if she lived for sixty years in prison, and never went home? What had she expected, going into her imprisonment?

There are some other places where Beauty’s expectations come into play, but that’s more a question for next time. (Ethics and themes and whatnot.) In the story, the reader is shown how Beauty stays brave and true, consistently turning down the beast throughout her confinement. But how—and when—does she change her mind about him?

What would her diary entries from this time in the story reveal about her plans for the future, her thoughts on the castle and her home?

*Stockholm Syndrome refers to a situation where a captive "falls in love" with his or her captor. This is a serious and dangerous psychological condition, usually accompanied by the captor manipulating the prisoner and forcing a false sense of dependency. Beware!

Thursday, March 15

Silver Hands and a Reliable Plot

Where last we left our heroine, you were cutting her into wafer-thin slices for a closer examination. Don’t be shy with your scalpel—anyone who can grow back an appendage or two must have enough alien in her to survive a plot breakdown.

Silver hands is a story full of symbolism and parable. We’ll come back to those topics at a later date—I only here bring it up because the symbolism in the story can help you find the hinge points of the plot.

Cinema’s three-act structure is an easy framework in which this story fits. (Where did it come from? Back in the day, movies were put on several reels of film. These reels had to be switched out by hand, and the theater employees who ran the projectors got bored or didn’t know when in the story the reels needed to be switched. So, movie producers changed the format of films to have three “acts.” As the climax of each reel became apparent, the person working the projector knew it was time to get the next reel ready. This format of having a cycle of three physical stories that told one emotional journey has become the prevalent modern mode of story-telling.) First act, we have the deal with the devil, the girl’s mutilation and subsequent ejection from home. Second act, we have her unexpected rescue by the king, their wholesome little marriage, and the shock of the devil’s interference. Third act, we have her husband’s desperate search for her, the new identity and miraculous recovery of her hands, and finally the reunion of the good girl and her faithful king.

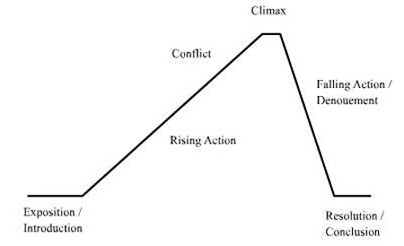

Sweet and simple. Dividing the story into the traditional plot graph—with its straight lines and uncompromising “before-and-after”—that’s a little harder. Using the symbolism to map the girl’s emotional journey helps.

The very first thing that happens in the story is the devil’s bargain with the girl’s father. Some students and writers might argue this is the inciting incident in the whole tale. Given that the reader hasn’t yet met the heroine, that’s a little premature. Although momentous and life-changing, the bargain is more of a set-up for events to come. (Keep in mind, we’re talking about a devil. He’s after the girl’s soul, which wasn’t her father’s to bargain with in the first place, so the devil will continue to pursue any chance to entrap the girl.)

A better place to put the plot’s inciting incident is when her hands are chopped off—it’s irrevocable, memorable, and marks her as unique for the rest of her life. This is another place where symbolism comes in handy—what do her clean, white hands matter when the devil wants more of her than that? (Future writers, look for these moments. When an author provides a situation or circumstance that makes the reader ask questions, these are usually clues to powerful and effective storytelling. Don’t be afraid to create questions in your own work.) The girl cannot stay in her parents’ home any more—partly because their bargain with the devil prevents her parents from offering shelter, but also because her character is sufficiently pure that she could not live in a house full of ill-gotten gain.

Good for her.

Her first venture into the forest, and her delicate thievery in the king’s orchard, start the reader on a slow accumulation of events. Both physical and emotional. When she is helpless, without friend or resource, the events are small and tug at the reader’s heart. As she gains the love and respect of a man of good family and greater resources, the circumstances and stakes begin to get larger. The impending birth. The far-off war. The devil’s interference. As the girl’s world expands to include people and situations other than her own personal drama, she begins to make choices to protect those she loves, instead of protecting herself. Though up and down in terms of intensity and emotion, these are natural escalations in the plot’s rising action.

Now, depending on your arguments and point of view, there are two possible places for the plot’s climax to be argued. One is here, where the girl flees into the forest with her infant son. You could argue that everything after this is self-explanatory. I could argue in turn that this is precisely why the heroine’s emotional journey is so important. Fleeing into the woods—again—solves nothing. The girl has a good heart and great character, but wisdom has been slow to come to this young mother. She has not yet learned when to flee from evil and when to stand her ground and fight. A wise girl would have fled her father’s home when she first learned of the bargain. Or stayed to face down her husband who dared to order the murder of their son. Supposedly.

Since wisdom is gained through experience and good counsel, I would hold off on the plot’s climax until the king finds her in the forest. She spends several years with good people who live in the dark and scary forest—they know not to run just because they are frightened. Not until the girl can exercise wisdom and bravery together does she get her happy ending.

When we (authors) develop stories, we seldom think in terms of graphs and analysis. We want to tell a story. Some adventure. A little mystery. Maybe some tingles. We can get very focused on the details of a character, an event, or how we see the threads of our story interweaving. But having a plot—a line on which to hang all the minutiae of our complicated story—this is an essential part of telling a tale.

What climax is your story climbing towards? What goals, fulfilled or otherwise, burn in your hero? What do your readers want out of the story? What do you want your story to tell, when it’s done? An unexpected miracle of renewed hands, or a deeper story of bravery and belonging? How will you get there from here?

Well, that’s a story for another day...

Monday, March 12

Silver Hands and...

While I still have several more of the “classic” fairy tales to go, I didn’t want to leave the question of Plot alone too long. This story is a lesser known tale, and the version I have summarized here is an amalgam of two of the better versions I’ve come across. You are welcome to do some research on your own. (Aarne-Thompson classifies it as type 706--"The Armless Maiden.") Since this is an older, less known story, some versions have elements that are unfamiliar to our modern sensibilities (in terms of morals, cultural norms, and symbolism).

Silver Hands—also called “The Orchard”—became one of my favorite fairy tales after I grew up. I never heard of it as a child (which is saying something, since I devoured fairy tales back in the day). Clarissa Pinkola Estes, who I’ve quoted before in this blog, does an extraordinary job of breaking this story into its pieces and parts in her book Women Who Run With the Wolves. I do not intend to dissect the story here, but this story is ideal for mapping out a plot.

Now, a clearly marked plot can be one of the hardest things for a writer to generate. We like a character, we like a scenario, we like an adventure, but breaking it into things like “rising action” or—heaven forfend —“mid-point” is sometimes asking too much. The classical plot structure with its asymmetrical graph is often still taught in schools.

Even when writers think it too simple for the complex details vying for attention, this version can help a writer think in a straight line. The evolution of film led to what is now called “the three-act plot structure”—a veritable minefield of clichés and predictable outcomes.

Don’t get me wrong. I like movies. When they’re good. I like structure and rules for stories. A six-hundred page run-on sentence about the difference between a pimple and a pickle would get old fast. Plot is a good idea.

The trouble is, an author needs the reader to want to be on the same roller coaster that she is writing. Which is why I’m using “Silver Hands” for this analysis. As you’ll see in the summaries page, I broke down and used an extra paragraph for this story. Partly because it is a long, richly textured story that deserves more attention than I gave it, but mostly because this story breaks almost perfectly into three acts. Looking at the events of the story can make it difficult to use the classical plot structure, though. Which event is the climax? How can we have an inciting incident before we’ve meet all the characters?

This is easily answered. For the classical plot structure of this story, examine the heroine’s emotional journey. Instead of three separate and intense stories, her emotions follow one straight line. In film, this is ideally what happens. A character undergoes a series of events that all tie into one emotional journey. I believe there’s actually a little more leeway in printed media (books, short stories, poetry, etc.), but the idea is the same.

Which is why the 3-act structure is used in helping writers construct their stories. For this week, take apart Silver Hands. Use the plot graphs given here (or that you find in your own research) to break the story into its acts and actions, upheavals and downswings, development and deconstruction.

Try it. You’ll like it...

Friday, March 9

Sleeping Beauty and Appropriate Antagonists

Where last we left our heroine, she had just settled in for a long winter’s nap. With a curse hanging over her head, but no hardships on the horizon, this princess has nothing better to do than to wait for her prince to give her life and meaning.

Yes, there are ladies who object.

No, they aren’t all “FemiNazis.”

True, the story of Sleeping Beauty does lack for proper villains. In the original German version, the long-awaited prince has nothing to overcome. What had once been an impenetrable fortress of thorns is now easily-mown straw (or flowers, in some versions). The French and Italian versions have villains on the other side of the princess’s wake-up call, but they are quite dark (check the uncommon version, if you haven’t already). But even there, the antagonists are external. Fairies who punish a baby for her parents’ mistakes. Jealous wives who want to hurt their husbands first, not “the other woman.”

Yes, evil forces in our lives often only want to hurt us because it will hurt someone who loves us. We’re the side dish of their revenge, not the main course. That doesn’t mean that readers don’t want to matter in their own drama. And while Sleeping Beauty is a classic, well-known fairy tale, I suspect this is where our young minds begin to rebel. We want more from a story than an inevitable, easy sleep and a prince who is charming, not sincere.*

Now, you were supposed to derive your own version of the story, with a proper antagonist. Someone who has a specific goal of thwarting or destroying the protagonist—the princess, in this case. Disney solved this problem in their cartoon by setting the fairies against each other. And since, in this version, the prince and princess had already met, “true love’s first kiss” was much more believable. Robin McKinley wrote Spindle’s End, a feisty version with a princess who takes matters into her own hands and fairies caught in a desperate game of outsmarting each other’s magic. (And—spoiler alert!—the princess does NOT wind up with prince charming. It’s a good story.)

There are a lot of adaptations—in print, in film, in dance, in art. As storytellers and story-readers, we need to see a villain overcome in a story. And there is a part of the human soul that wants it to be a worthwhile fight. And easy or uneven battle holds very little interest for us—especially at the end. We want the win to be epic. A climax that rights all wrongs, or restructures the universe, or pushes two people who belong together into each other’s arms.

But that’s a story for another day...

*This is a quote from Steven Sondheim's mixed-up fairy tale musical Into the Woods.

Labels:

Antagonist,

Axiom,

Disney,

film,

Robin McKinley,

Sleeping Beauty,

Sondheim,

villain

Monday, March 5

Sleeping Beauty and...

One of the few Sesame Street skits I remember clearly from my childhood was one of Kermit the Frog’s investigative reports. He was interviewing the three parts of every story: the beginning, the middle, and the end. Both the beginning and the end were angry with the middle for taking up so much of the story. The poor middle kept getting left out, because the end wanted his turn.

You may call me unfair, because I don’t intend to talk about plot structure here. I could, but that’s a story for another day. Yes, really. The story of “Sleeping Beauty”—especially as it is known today—is not the best choice for breaking down a tale in such a fashion. I have a good one up my sleeve for that. Later.

Sleeping Beauty is a classic staple of nurseries. Some of the phrases or concepts from it have made it into our everyday conversation. Girls who sleep deeply. The dangers of spindles. The longevity of curses. Prince Charming’s first kiss.

Curiously enough, the last fairy’s inability to properly counter the bad fairy’s curse is seldom dwelled upon. Which may be for the best. Otherwise, the reader might start to wonder about other thin spots in the story. The way the Prince just...rode on into the abandoned castle, for example. No one to fight, nothing to overcome.

Sleeping Beauty, as we know it, is largely a story without antagonists.

Oh, we could argue that the wicked fairy was an antagonist. Quite convincingly. But was she ever overcome? Disney certainly rewrote the story so there were moments of heroism and conflict. To my mind, it’s certainly a more palatable version than some stranger showing up and kissing awake the girl.

Why did I start with the beginning, middle, and end, then? Because there are older versions of the Sleeping Beauty story that tell more. Parts that were understandably left out. (See the uncommon version here.) The Sleeping Beauty we know today is only about the first half of the older version. The clean half, many would say. Rather like Sesame Street’s interrupting ending.

Now and again over the last month or so, we’ve touched on “the bad guy.” Antagonists are valuable parts to the story. They are pretty firmly excluded from the current version of the story. That doesn’t prevent Sleeping Beauty from being told and remembered. But I do believe it is a factor in why we abandon fairy tales as we get older. We want our heroes to overcome something. Someone, often.

More on this next time, but how could “Sleeping Beauty” be told with a proper antagonist? Try and come up with a version of your own.

Friday, March 2

Rapunzel and Her Bad Self...

Where last we left our heroine, she was making her own trouble.

Hey, don’t look at me like that. She was. Yes, her parents sold her to a witch. Yes, said witch locked her away. None of that means Rapunzel wasn’t responsible for her own decisions.

Nobody said she had to let down her hair for the Prince. Nobody said she had to do him any favors. And certainly nobody said she was under some sort of obligation to let him in again—repeatedly. Nothing prevented her from saying “Come back when you’ve got something for me, baby.” Indeed, in the earliest version the Grimm brother collected, Rapunzel spilled the beans to the witch when she complained of pregnancy symptoms. Rapunzel, clearly, is neither clever nor innocent.

Not that all her troubles should be laid at her door.

This was the first “boy” she’d ever seen. First thing we girls often look for in the is that age-old question—“Can I marry him?” We don’t all do it, but we do come naturally warped that way. So, she sees a fella in her tower window, and he wants to see more of her. How is she to say no to that??

Plenty of responsibility is due his way, though. He should have asked some very pertinent questions. What’s your mom doing, keeping you here? Why do you let her in, if all she does is lock you away? Did there used to be a door? He knew from the start he was walking into a dysfunctional family—he should have been paying attention. But this begs the question of his motives. If the prince was there for her, then he should have indicated a plan to rescue her and help her establish a new home.

But when he meets Rapunzel and declares his love, he doesn’t rescue her. He keeps her in her tower, and comes back to visit. Often. As convenient as it is for him to find a pretty girl in the woods who thinks he’s wonderful and stays right where he leaves her, this isn’t responsible behavior. So, when the witch discovers their shenanigans and exacts her punishment on both of them, the reader is willing to follow along. The reader does not cry “unfair!” and hurl curses at the witch. The reader’s imagination follows the boy and girl out the window into the next phase of their adventure.

However sad or hopeful that may be.

As writers, creating characters who your readers love—EVEN IN FAILURE—is quite a challenge. Giving them flaws that cause their problems helps. Making these flaws things that can be overcome helps, too. (The Greeks had a word for this too: HAMARTIA. It means "a wrong committed in ignorance." It is sometimes used in the Bible to mean "sin," in the context of a moral deficit.) Cinderella and Snow White had their circumstances against them—Rapunzel has her own character to overcome. And, clearly, a girl who can unlearn her mistakes is a girl worth climbing a tower for.

Tuesday, February 21

Rapunzel and...

There once was a fair maiden, imprisoned

through no fault of her own... Very appealing concept. Many aspects of the “Rapunzel”

story work for the human imagination. The girl must be beautiful. The witch must

be evil. Whoever saves her must be a prince. It’s a story that readers easily

invest themselves in, letting their imaginations trot cheerfully alongside the

plot. If the story takes an unexpected turn, the reader doesn’t balk.

Why?

This is a story with thin spots. And places where readers really should think for themselves.

What’s the deal? How is it that centuries of perfectly sensible people would

tell and retell this story? Snow White had helpless innocence going for her.

Cinderella had that persecution thing down pat. What does Rapunzel have?

Rapunzel

has a set of parents who make poor decisions—both for themselves, and for their

child. Sad, but true. What else? Rapunzel has a witch—who, by default, must

have wicked motives at heart. What kind of mother imprisons her child? (Parents

of teenagers, feel free to chime in...) Rapunzel has a prince—who must be young

and handsome. Who wants her tower breached by a slobbery old guy? And

Rapunzel has a fair maiden—who needs to be rescued.

This

is a story that’s been rewritten a time or two, especially in recent times. (Disney princess, number 10) Certain elements of the story stay

in, others are inevitably changes. Usually to make Rapunzel more of a “go-to”

girl—someone who does more herself, instead of waiting for a savior.

And

yet...there are other aspects of the story that are impossible to sweep under

the rug, toss out the window, or tastefully erase. Perhaps because the writers

aren’t paying attention, but also perhaps because the reader wants these aspects

in the story.

Flawed

characters.

This,

I suspect, is where Rapunzel gets its mojo. The prince may be young and he may

be charming, but nobody ever said he was perfect. Rapunzel herself isn’t the

pristine, innocent girl found in many of the commonly known fairy tales. Most

fairy tales center on characters placed in a set of circumstances. This is a

story about characters who generate the plot, instead of being taken over by it.

More

on this later, but can you think of stories with characters who make their own

trouble? Where the story hinges on the characters putting themselves in sticky

situations, even if for the right reasons?

Friday, February 17

Red Riding Hood and an Alternate Ending

When last we left our heroine, she was about to judo-chop the wolf. Be honest—how many of you thought Hoodwinked was a valid rewrite? In that case, what starts as an awkwardly perky musical ends as a well-intentioned crime scene investigation. For fuzzy animals. Who love good health and happy endings.

Moving right along...

How we—any author—rewrite a story like "Red Riding Hood" begins with perspective. Yes, it will end with an ending. Somewhere, out there. But first the question of the writer's preconceptions and understandings must be examined.

A child who reads the story may come away thinking, "Wolves are bad. I shouldn't talk to strangers." A young woman who reads the story may come away thinking, "Wolves are bad. Where can I get one?" A grown woman who reads the story may come away thinking, "Wolves are bad. No child should even know they exist."

Unwholesome possibilities, to be sure.

But a child who wants to rewrite the story will want characters like an interfering woodsman, a caring grandmother—someone to step in and FIX the story. If little Red is a girl in trouble, then she is a girl who needs to be rescued. Grown-ups should care enough about children to look out for them, right?

Many modern retakes of the story involve, like the satire link last time, a girl who saves herself. Red knows karate, or brews her own pepper spray, or ties up the wolf and sells him for thirty pieces of silver. The "I don't need YOUR help" mentality makes for a very one-sided story, and will have a profound impact on what kind of options are available for an ending.

I will not be discussing people who want to side with the wolf. That falls under the category of dark fantasy. It's not inconceivable to change the story to defend his point of view, it's just not something I want to encourage. Or, frankly, have time and space to do the argument justice. Maybe later.

In its purest, simplest form, this story is told from an omniscient point of view. This means that the reader sees what’s going on in every scene and is privy to the actions and thoughts of all characters. To choose a side—whether it is young Red or the wicked Wolf—is to shift the point of view. And in so changing how the story is seen, the author changes all possible outcomes. Before picking sides with the little girl, Grandma could have become the hero. Once the author decides to favor the child, though, the story must have an ending that satisfies the needs of the chosen character.

All this is not to say that bad creatures never star in fairy tales. I can think of several fairy tales that deal with people falling into blackest witchcraft and never coming out. But they don’t give the reader anything new to think about. And they don’t feed an author’s soul the way that a properly magical story should. Filling you with possibility, and imagination, and the fantastic union of shared imagination.

Which is why some authors keep coming back to the wolf and his red-caped prey. “Surely there must be a way to resolve this story in a matter that feeds me...”

And surely there is. But that’s a story for another day...

Moving right along...

How we—any author—rewrite a story like "Red Riding Hood" begins with perspective. Yes, it will end with an ending. Somewhere, out there. But first the question of the writer's preconceptions and understandings must be examined.

A child who reads the story may come away thinking, "Wolves are bad. I shouldn't talk to strangers." A young woman who reads the story may come away thinking, "Wolves are bad. Where can I get one?" A grown woman who reads the story may come away thinking, "Wolves are bad. No child should even know they exist."

Unwholesome possibilities, to be sure.

But a child who wants to rewrite the story will want characters like an interfering woodsman, a caring grandmother—someone to step in and FIX the story. If little Red is a girl in trouble, then she is a girl who needs to be rescued. Grown-ups should care enough about children to look out for them, right?

Many modern retakes of the story involve, like the satire link last time, a girl who saves herself. Red knows karate, or brews her own pepper spray, or ties up the wolf and sells him for thirty pieces of silver. The "I don't need YOUR help" mentality makes for a very one-sided story, and will have a profound impact on what kind of options are available for an ending.

I will not be discussing people who want to side with the wolf. That falls under the category of dark fantasy. It's not inconceivable to change the story to defend his point of view, it's just not something I want to encourage. Or, frankly, have time and space to do the argument justice. Maybe later.

In its purest, simplest form, this story is told from an omniscient point of view. This means that the reader sees what’s going on in every scene and is privy to the actions and thoughts of all characters. To choose a side—whether it is young Red or the wicked Wolf—is to shift the point of view. And in so changing how the story is seen, the author changes all possible outcomes. Before picking sides with the little girl, Grandma could have become the hero. Once the author decides to favor the child, though, the story must have an ending that satisfies the needs of the chosen character.

All this is not to say that bad creatures never star in fairy tales. I can think of several fairy tales that deal with people falling into blackest witchcraft and never coming out. But they don’t give the reader anything new to think about. And they don’t feed an author’s soul the way that a properly magical story should. Filling you with possibility, and imagination, and the fantastic union of shared imagination.

Which is why some authors keep coming back to the wolf and his red-caped prey. “Surely there must be a way to resolve this story in a matter that feeds me...”

And surely there is. But that’s a story for another day...

Monday, February 13

Red Riding Hood and...

This, I confess, is an irresistible classic. "Little Red Riding Hood" has tremendous appeal, and has been retold time and again. Each author changes it to suit his or her interests. Odd "interests" in many cases, but people continue to be drawn to the story.

As an author, one has to wonder "Why?"

What does this fairy tale have going for it, that it should be so readily adaptable and that people would continue to want to adapt it? Stories like Cinderella appeal, certainly, but for different reasons. People--yes, usually women--want to identify with Cindy. Red Riding Hood is different. It seems to be retold most often because people DON'T like it, rather than because they do.

In all honesty, this is why many of us embark on the journey of writing. We want a story with an ending that satisfies us. When faced with a story we don't like as much, the temptation of revising it to suit our standards is great.

Now, here is a link to most of the early versions of this story. Historians are quick to point out that there might be older versions, but none were recorded in this format (girl, grandmother, wolf, and woodsman) before the seventeenth century. My absolute favorite version of this story is a more modern satire, which can be found here. I like this because it has an absurd ending, that tells the reader more about the topsy-turvy world inside the author's head than it tells about how people (or the world) really work.

There are a lot of wonderful places this story can take a young author. The heroine's responsibility for bringing trouble upon herself. The gullibility of the womenfolk. The wolf's intentions (and inhibitions). The need (or lack thereof) of a savior like the woodsman.

My question for you this week, is which character would you like to rewrite most? Why? How would you do it?

As an author, one has to wonder "Why?"

What does this fairy tale have going for it, that it should be so readily adaptable and that people would continue to want to adapt it? Stories like Cinderella appeal, certainly, but for different reasons. People--yes, usually women--want to identify with Cindy. Red Riding Hood is different. It seems to be retold most often because people DON'T like it, rather than because they do.

In all honesty, this is why many of us embark on the journey of writing. We want a story with an ending that satisfies us. When faced with a story we don't like as much, the temptation of revising it to suit our standards is great.

Now, here is a link to most of the early versions of this story. Historians are quick to point out that there might be older versions, but none were recorded in this format (girl, grandmother, wolf, and woodsman) before the seventeenth century. My absolute favorite version of this story is a more modern satire, which can be found here. I like this because it has an absurd ending, that tells the reader more about the topsy-turvy world inside the author's head than it tells about how people (or the world) really work.

There are a lot of wonderful places this story can take a young author. The heroine's responsibility for bringing trouble upon herself. The gullibility of the womenfolk. The wolf's intentions (and inhibitions). The need (or lack thereof) of a savior like the woodsman.

My question for you this week, is which character would you like to rewrite most? Why? How would you do it?

Friday, February 10

The Six Swans and the Good Guys

Where last we left our heroine, you had her pinned up a tree and were preparing to deconstruct every bit of fun out of her. All without her saying a word. I hope you had fun.

You may have come up with different character traits than what follows. That doesn’t make you wrong. With any written work, a lot of different ideas can be extrapolated from a character's words or actions. Not all of them can be reasonably supported by the whole text. But just because one person presents an argument, that doesn’t mean you can’t come up with a different, equally sensible one.

Because the readers meet the princess first, let’s begin with her. As a protagonist (another ancient Greek theater term, meaning “one who plays the first part” or, more simply, “the chief actor”) is the character that the author most wants the reader to identify with, it makes sense to give more of the princess’s back story. Of course, since she will not have a speaking part for most of the story, the reader needs good reason to cheer for her.

First off, she is good. Modern audiences often put down the “old-fashioned” idea that a main character must be a good guy. This princess, however, has words and actions that support this label. In the beginning, when she knows something bad lives in her home, she flees. Fear is a perfectly good reason to run, of course, but we would think her foolhardy and craven if she stayed. There comes a time, both in stories and in life, when a good guy must get out of a bad situation.

But she isn’t just running away. The princess is looking for a way to save her brothers. This is important, because what she’s not doing is looking for a way to defeat her stepmother. She’s not dwelling on the evil that has infiltrated her family—she’s just focused on rescuing the innocent. To obsess over the stepmother would allow that toxic woman to have power in her life. No, thank you. All of these actions and choices demonstrate her goodness, and set a foundation for the reader to like her as she foregoes speech.

Second, she is diligent. The princess searches for her brothers until she finds them. Then she takes up the very difficult task of making cloth from nettles. (The full-grown weeds have a woody stem, filled with long fibers that can be dried and woven like linen. It makes a cloth that is thinner than silk.) And she sticks to her task until she finishes. Someone reading this can simply scoff at the idea of setting a heroine to an impossible task (like silence), but this girl is persistent. She keeps at the work until it is done. In Germanic culture, industriousness is a very valuable character trait. Making it praiseworthy in a story is a natural part of a fairy tale.

Lastly, she is faithful. This ties in with both her goodness and her diligence, but it is demonstrated more the further into the story we read. She does not have to choose to save her brothers. Having taken up that cross, she tells no one what she’s doing. When she marries the king, she could abandon her project. But she doesn’t. When her mother-in-law brands her a witch, a few words would free her. But she stays the course.

And her husband, to whom she has never spoken, seems to recognize these qualities without knowing her back story. In a lot of the well-known fairy tales, the hero and heroine are not well-matched. The reader knows a lot more about one character than another, and what is learned of these characters isn’t always detailed or particularly deep. Not in this case.

First off, the king is honorable. This is not a given in fairy tales. Some princes are not as charming as we assume. However, this time we have a winner. When the king finds the girl alone in the woods, nothing suggests she is a rich princess. He never looks for her family or father, so we can assume he had no reason to do so. But when he takes her home, he marries her. No one is holding a gun to his head on this decision. He could have locked her in a tower somewhere, without marrying her. (Yes, that happens in some fairy tales.) She did nothing to encourage his pursuit of her in the forest, but he gives her a home and the protection of his name. This indicates he has a deeply ingrained code of ethics that help make him a worthy leader.

Second, he is just. This is also a quality that shouldn't be assumed. Plenty of people, be they leaders or small fry, will duck responsibility if they don't like the consequences. When his wife is accused of witchcraft, the king puts her on trial. He's not doing this to punish her for her silence. The law of the land demands it, and this king is not going to ignore the law or abolish it just because he doesn't like it. There are a lot of modern...let's call them "celebrities" (some hold elected office, some are appointed by elected officials) who do not exhibit this character trait. Whether by choice or by ignorance. However, here we have a king who serves his laws, rather than a man who uses the law for his own gain.

Lastly, this king is loyal. This element of him is more personal and complements the princess's character very well. When he imprisons his wife and puts her on trial, he sits with her in the dungeon every day, asking her "What happened?" Nowhere in the text are we given the idea that the king believes the charge of witchcraft. But he does not abandon his wife just because she's in trouble. He has chosen a wife whose history and priorities he doesn't know, but he doesn't leave her when her loyalties are tested.

Like I said, this fairy tale is one of my favorites. (Clearly, I can blather on and on about it ad nauseum.) If you're going to read fiction, it should leave you better than when it found you. Later on, we'll dive into bad guys and other modern conventions, like making bad guys protagonists or writing flawed characters. Useful, realistic even, but not always uplifting.

But that's a story for another day...

Second, he is just. This is also a quality that shouldn't be assumed. Plenty of people, be they leaders or small fry, will duck responsibility if they don't like the consequences. When his wife is accused of witchcraft, the king puts her on trial. He's not doing this to punish her for her silence. The law of the land demands it, and this king is not going to ignore the law or abolish it just because he doesn't like it. There are a lot of modern...let's call them "celebrities" (some hold elected office, some are appointed by elected officials) who do not exhibit this character trait. Whether by choice or by ignorance. However, here we have a king who serves his laws, rather than a man who uses the law for his own gain.

Lastly, this king is loyal. This element of him is more personal and complements the princess's character very well. When he imprisons his wife and puts her on trial, he sits with her in the dungeon every day, asking her "What happened?" Nowhere in the text are we given the idea that the king believes the charge of witchcraft. But he does not abandon his wife just because she's in trouble. He has chosen a wife whose history and priorities he doesn't know, but he doesn't leave her when her loyalties are tested.

Like I said, this fairy tale is one of my favorites. (Clearly, I can blather on and on about it ad nauseum.) If you're going to read fiction, it should leave you better than when it found you. Later on, we'll dive into bad guys and other modern conventions, like making bad guys protagonists or writing flawed characters. Useful, realistic even, but not always uplifting.

But that's a story for another day...

Labels:

Axiom,

Characterization,

Details,

Fairy Tale Genre,

Politics,

Protagonist,

Six Swans

Tuesday, February 7

The Six Swans and...

All right, on to the good stuff. Yes, I’ll come back to Ruth. Yes, I’ll do more with Cinderella—particularly this neat American Indian version I came across. However, I love the out-of-the-way fairy tales. This is a particular favorite.

Not because it puts me in the role of a story-teller. (If I’m going to rattle on and on, wouldn’t it be better to tell a story of my very own?) No, “The Six Swans” has a magic that is deeper than witchcraft and better than a warm fire on a cold night. But it is important to use the early Grimm’s edition of this story. There are variants with three brothers (The Three Ravens), or even twelve (The Twelve Brothers), but these versions lack the powerful writing tools hidden in The Six Swans. Even in the short version posted here, what makes this story spectacularly useful is still easily obvious.

Betcha didn’t even notice, did you? That’s ok. You kind of have to know where to look.

See, the beauty of “The Six Swans” isn’t in its archetypes, or its formulas, or any of the handy-dandy guidelines storytellers are encouraged to study. This is a fairy tale with sympathetic characters. The reader wants to love the princess, and is easily persuaded to do so. The reader wants the young king to be charming, and is given no reason to think otherwise of him.

We would love the princess if she were saving three brothers or twelve—or even one. It would be...well...wrong...of a reader NOT to love a character willing to sacrifice for someone else. Saviors, whether they succeed or fail, are easy to cheer for. The king’s character becomes stronger and sweeter, the deeper into the story we go. At first, he could be any good guy in any fairy tale. As the story begins to take some serious turns, though, he blooms into something more serious himself.

Not being very specific, am I?

That’s because I want you to take a stab at this one. You can look up another version online, though I’m old-fashioned enough to recommend an actual book. Read this story, study these characters. There are unique qualities to the two main characters that make them easily remembered and eminently worth taking with you. Home from the library, or incorporated into the baggage of your soul. Look, and you will see what makes them “good guys.”

Yes, of course I’ll have an answer Friday. Doesn’t mean you can’t analyze some characters yourself...

Saturday, February 4

The Sparrow's Gift and Some Spare Change

Where last we left our heroine, she was a bitter, spiteful harpy who saw her faults in everyone around her. Who wants to feel any sympathy towards that?

The answer, of course, is no one.

The wonder and the charm of this fairy tale begin when the old woman changes. It’s the last paragraph of the story. In some versions of “The Tongue-Cut Sparrow”, the story ends when she opens the box of demons. No change necessary for the character in that version. (Didn’t read it the first time around? It’s here.)

This story made me think of several other stories—all of whom have a character who waits until the last minute to change. In some of these stories, it’s believable and even long-anticipated by the reader. But in some of these stories, the change is never noted by the reader. People walk away from the story saying “that’s a bad, bad guy” rather than celebrate the wonder of a life in revolution. Depending on the story, this takeaway value can be either the reader’s fault—or the author’s.

In the Old Testament, the books of Kings and Chronicles both give historical accounts of the same time period, the same events, the same people. If you’ve never heard of King Manasseh, take a minute to read about him here. Most people, insofar as I know, are more familiar with this account. As you can see, he repents in one, but the other ends with God Himself cursing him. I can understand that it is convenient for people to remember him only as a wicked king, but men can be defined by a single moment in their lives, too. The moment he led the team to victory. The moment he turned from a good life, and was stricken with leprosy. The first time he said “I need help!”

These single moments are vital to us. Our lives are frail. Yes, we can trudge endlessly down the same path, never changing our steps or even looking up. That doesn’t mean we won’t look up on the next step, or turn back in the next heartbeat. Humanity is built on such hopes. The times when we turn around or climb to a peak we had considered impossible should be celebrated. Even if only in brief memories.

Characters, however, don’t seem to have that luxury. Words may not be set in stone, but—with a few lines of black ink on a white page—they can carve a complete person into the reader’s imagination. If the words are chosen wrong by the writer, the reader may never know it. But the reader has chosen to accept the writer’s words as an important part of his imagination, so it behooves the writer to give a character enough time to change on the page.

In a short story, like a fairy tale, the last page is enough room to change. Usually. With this fairy tale, the author is helped by the fact that the character’s change is unexpected—because it is sweeter. It’s a welcome surprise, that leaves the reader smiling. For a longer story, the writer has two problems:

1. How far into the story must I carry this character before changing her?

2. Do I owe it to my readers to make the reader want the character to change before it happens?

How do you solve these questions in your stories? These are hard questions for writers anywhere, and there aren’t easy answers. Only guidelines. More or less. But that’s a story for another day...

Tuesday, January 31

The Sparrow's Gift and...

Given the plethora of Hansel and Gretel variants that are airing on television, I had expected to tackle another familiar tale this week. This Japanese story enchanted me, however, and struck some deep chords. So, into the wild I go. Please join me...

“The Sparrow’s Gift” is a fairy tale with a character who changes, which is somewhat rare in fairy tales. We are so used to “stock characters” in fairy tales—evil stepmothers, ugly stepsisters, damsels in distress, etc.—that a story whose whole purpose is the turning of a character seems out of place. These stock characters are easier for youngsters to identify with, so they are the stories we ask for in nurseries and at bedtime. This story, however, is for grown-ups.

Not because it is so worldly or filled with dangerous themes. Rather, because young audiences seldom appreciate patience or kindness towards those who do not deserve it. Many of us cheer when Cinderella’s stepsisters get their eyes pecked out. We want Baba Yaga’s chicken-legged house to eat her up, rather than torment the brave youth. The old woman in this story, however, isn’t eternally punished for her evil deeds. She is exposed to the error of her ways and then—much to our surprise—proceeds to change.

What kind of evil witch is this?

She’s a person, silly. It is easy to blame evil on others when we are young, for bad things surely cannot be our fault. When we are grown, though, we no longer have that excuse. Bad things may happen to us, of course, but a part of growing up is accepting responsibility for the consequences of our actions. The expression “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks”—meaning people become set in their ways and are incapable of change—is a convenient lie the lazy give to keep from being responsible.

If this old woman could change, why can’t you? Or I, for that matter?