While I still have several more of the “classic” fairy tales to go, I didn’t want to leave the question of Plot alone too long. This story is a lesser known tale, and the version I have summarized here is an amalgam of two of the better versions I’ve come across. You are welcome to do some research on your own. (Aarne-Thompson classifies it as type 706--"The Armless Maiden.") Since this is an older, less known story, some versions have elements that are unfamiliar to our modern sensibilities (in terms of morals, cultural norms, and symbolism).

Silver Hands—also called “The Orchard”—became one of my favorite fairy tales after I grew up. I never heard of it as a child (which is saying something, since I devoured fairy tales back in the day). Clarissa Pinkola Estes, who I’ve quoted before in this blog, does an extraordinary job of breaking this story into its pieces and parts in her book Women Who Run With the Wolves. I do not intend to dissect the story here, but this story is ideal for mapping out a plot.

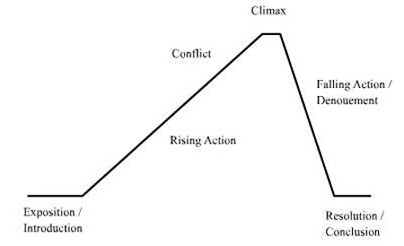

Now, a clearly marked plot can be one of the hardest things for a writer to generate. We like a character, we like a scenario, we like an adventure, but breaking it into things like “rising action” or—heaven forfend —“mid-point” is sometimes asking too much. The classical plot structure with its asymmetrical graph is often still taught in schools.

Even when writers think it too simple for the complex details vying for attention, this version can help a writer think in a straight line. The evolution of film led to what is now called “the three-act plot structure”—a veritable minefield of clichés and predictable outcomes.

Don’t get me wrong. I like movies. When they’re good. I like structure and rules for stories. A six-hundred page run-on sentence about the difference between a pimple and a pickle would get old fast. Plot is a good idea.

The trouble is, an author needs the reader to want to be on the same roller coaster that she is writing. Which is why I’m using “Silver Hands” for this analysis. As you’ll see in the summaries page, I broke down and used an extra paragraph for this story. Partly because it is a long, richly textured story that deserves more attention than I gave it, but mostly because this story breaks almost perfectly into three acts. Looking at the events of the story can make it difficult to use the classical plot structure, though. Which event is the climax? How can we have an inciting incident before we’ve meet all the characters?

This is easily answered. For the classical plot structure of this story, examine the heroine’s emotional journey. Instead of three separate and intense stories, her emotions follow one straight line. In film, this is ideally what happens. A character undergoes a series of events that all tie into one emotional journey. I believe there’s actually a little more leeway in printed media (books, short stories, poetry, etc.), but the idea is the same.

Which is why the 3-act structure is used in helping writers construct their stories. For this week, take apart Silver Hands. Use the plot graphs given here (or that you find in your own research) to break the story into its acts and actions, upheavals and downswings, development and deconstruction.

Try it. You’ll like it...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please, have an opinion. You are welcome to all the room to talk you want. Just be aware, all comments are moderated. The author reserves the right to have your grandmother look over your shoulder and be proud of you.